Inventing a Better Insect Trap

min read

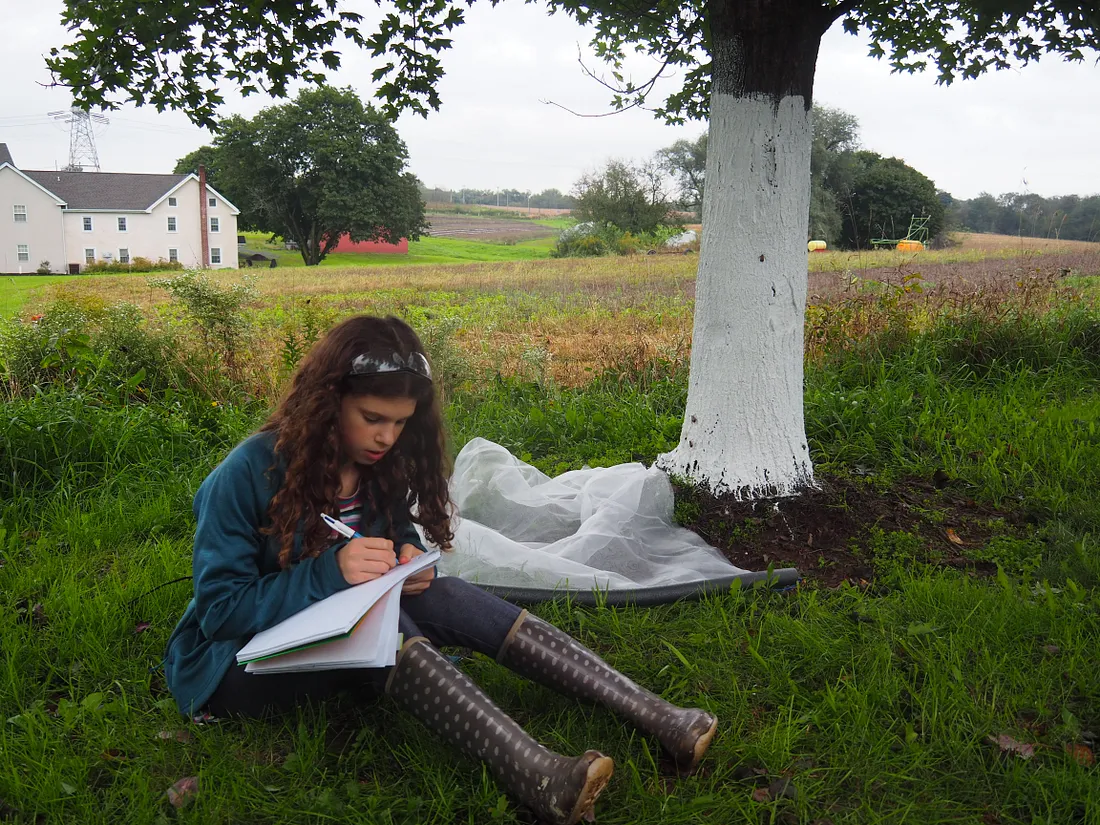

How One Pennsylvania Teen Found Inspiration in Her Own Backyard

How do you quash an insect invasion that threatens your favorite trees? For fourteen-year old Rachel Bergey of Harleysville, Pennsylvania, the answer involves inventing a new product out of garden netting and aluminum foil, and one key strategy: outsmarting the enemy.

The spotted lanternfly is an invasive species native to Asia that was first discovered near Philadelphia in 2014. The winged insect has since damaged trees, plants, and fruit crops throughout southeastern Pennsylvania and is estimated to cost the region $50 million each year.

Rachel first noticed the bugs while climbing the maple trees on her family’s farm. “I love climbing trees,” she says, and so it disturbed her to find their trunks and branches crawling with spotted lanternflies. “At some points you couldn’t even see the bark.” Right away she knew something was wrong.

Her efforts to save her local trees from the insects using an innovative and eco-friendly trap won the Lemelson Award for Invention at the 2019 Broadcom MASTERS (Math, Applied Science, Technology, and Engineering for Rising Stars), a top science competition for middle schoolers in the U.S. A program of the Society for Science & the Public, the competition is sponsored by the Broadcom Foundation with the aim of inspiring young scientists, engineers, and innovators to solve local and global challenges.

Rachel, who is home schooled, brainstormed with her mother and began weighing various methods to address this problem in her own backyard. “I wanted to save our trees or at least help take more stress off of them,” she says. After ruling out chemicals — too environmentally risky — and chopping — too heartbreaking — she decided to try wrapping the trees in sticky tape. Though a common pest-fighting tactic, it ultimately proved problematic. The tape required constant replacing, and it sometimes caught harmless animals like butterflies and even birds.

“I wanted to save our trees or at least help take more stress off of them,” she says. After ruling out chemicals — too environmentally risky — and chopping — too heartbreaking — she decided to try wrapping the trees in sticky tape.

But from her sticky tape experiments Rachel learned two crucial things about spotted lanternfly behavior. “I noticed that they had an instinct to only go up and not down, and it was very strong,” she says. “And I also noticed that they were attracted to darker surfaces.” Using this information, she began working with different materials to build a trap.

Finally, after “lots of trial and error,” she landed on a novel design made with garden netting, aluminum foil, and duct tape. By wrapping the tree trunk with foil and creating a hole paved with black duct tape, Rachel created a trap for the lanternflies. Because the tape is dark, the bugs are attracted to it and crawl along it, up through the opening in the foil, where they are eventually caught in garden netting. The only way out for them, says Rachel, is to crawl back down — something spotted lanternflies seem naturally averse to doing.

Not one to waste time, Rachel already has a patent on her trap and is in the process of tweaking and refining her design. Winning the Lemelson award, she says, was particularly meaningful. “When I heard that Mr. Lemelson had so many patents, it just really kind of spoke to me. I have a patent on my invention and I really saw him as an inspiration. And when I was reading about that award I was like, ‘That would be so amazing to win that.’”

Down the road Rachel is considering making a DIY video to teach other people how to fashion her trap themselves. She also dreams of one day working with a manufacturer to produce her invention on a larger scale. No matter what iterations may come, she says, the eco-friendly aspect of her design will remain. “We have such a beautiful world, and I think it’s definitely very important that we’re good stewards of it.”

Lisa Reichley, a local science teacher, mentored her as she developed her invention, and helped by showing her how to create a science board to present her research. Rachel says her mom was also an important source of support. “She was just always there encouraging me.”

Rachel encapsulates the traits of young inventors today — combining many different interests with a keen sense of observation. When she’s not busy climbing trees or inventing insect traps, she loves to swim, ski, ice skate, and play the violin. If all we do is look “down at our screen,” she says, “we’ll never really be able to look outside and see what are the issues around us.”

So, her advice to other young inventors like her is this: “Be observant, and when you do see an issue, try and solve it. And know that you don’t have to be a genius to do something — you just need to be passionate about making things better.”

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.