Fighting Infant Mortality Through Hypothermia Detection

min read

Narain’s TempWatch bracelet, a wearable device that monitors a newborn’s temperature.

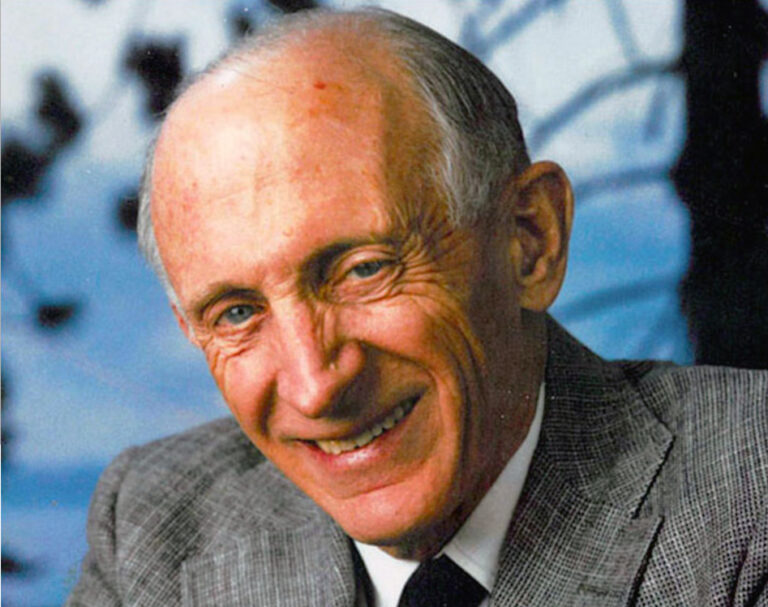

Biomedical engineer Ratul Narain’s monitoring devices help detect hypothermia and other illnesses in underweight newborns.

Every year, 20 million clinically underweight babies are born worldwide. Of these, eight million are born in India, where many parents don’t have easy access to neonatal care resources. Yet low birth weight — generally defined as less than five pounds, eight ounces — makes newborns vulnerable to a variety of potentially fatal complications, including infection, breathing problems, and hypothermia.

“It’s not a clear, this-is-how-you-solve-it type situation,” says biomedical engineer Ratul Narain. “Those babies aren’t necessarily born premature; they’re just born small.”

Narain — who was raised in the U.S. and graduated from Stanford in 2006, and is now based in Bangalore — is at the forefront of reducing neonatal mortality in India and other low- and middle-income countries. His company, Bempu Health, was first launched in 2014 to create an inexpensive, wearable device to address hypothermia in infants.

Narain’s TempWatch bracelet, which was tested in India, won funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Grand Challenges Canada, and USAID’s Saving Lives at Birth program to help accelerate its use globally. In 2017, Time magazine named it one of the world’s top 25 inventions.

We spoke with Narain about Bempu, the TempWatch, and his other innovations helping newborns survive.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to invent a device for newborn babies?

About ten years ago, I was spending time in hospitals in Karnataka, Bangalore, for research. One morning, a parent came in with her baby, who was deceased. The baby had been discharged from the NICU earlier, doing fine, free of infection, and feeding well. The doctor I was working with told me, ‘The only reason I can think of why this baby died is that it got too cold (hypothermic) at night while the parents were sleeping.’ It was a gap that really needed to be addressed, and that doctor was an inspiration for me because she said, ‘You have to build something to help with this.’

You started as an engineer — what led you to be spending time with neonatologists in India?

At Stanford, I was interested in the Design for Extreme Affordability program, and through that I got recruited to work for Johnson & Johnson, where I got a lot of training on how to make medical devices. I was in this new product development group and there was a lot of opportunity to brainstorm ideas for impact and talk to doctors — a little bit of a sweet spot that gave me the experience between what it takes to commercialize and get something on the market, do clinical trials, but also make changes or come up with something new.

Then in 2012, I left California to work as an engineering manager for a social enterprise called Embrace — that’s how I got to India about ten years ago. Then I started hanging out in hospitals, talking to doctors, shadowing nurses, seeing parents, and kind of understanding why there was such a high mortality and injury rate for babies in India. That field research led to a number of ideas for products which I vetted with doctors, and the one that was the simplest — now Bempu’s TempWatch — was the one that doctors liked the most.

What is the TempWatch?

Our design requirement really was that mom at that hospital in Karnataka, and the lower-income population in general. We had to figure out a way that these babies wouldn’t get hypothermic. Eventually I came up with the idea that we just make a simple way for caregivers to monitor and if the baby gets cold, we will alert them.

There’s actually a predecessor device called the Thermo Spot sticker, which was a public health innovation, but it had certain challenges — it could catch hypothermia, but you had to tell the parent to look. And hypothermia often happens at nighttime, when it’s too dark to see. It wasn’t very practically implementable, although it was cost effective and a very innovative device. So, taking that as inspiration, we developed the TempWatch, which is an easy-to-clean, silicone bracelet that monitors the newborn’s temperature, day and night, for one full month.

So the bracelet was originally designed for the Indian context. Can you describe how it works?

Parents sleep next to their babies in India. If the baby is warm, the device blinks a steady blue light, not too bothersome to disturb the sleeping parents. But if the baby is cold or hypothermic, it starts blinking a red light and it plays a tune that’s loud enough to wake up the mother or the father, so they can warm the baby before blood sugar and oxygen become compromised.

Funding for hardware-based companies is often limited to the R&D phase, but you received significant grants for the later stages, including manufacturing and in-market testing. How did this help the TempWatch get off the ground?

For me, I think the biggest risk has always been sales and the business model. So I really pushed our team to launch as quickly as possible, just so we could start getting feedback. We were fortunate that funders saw this as a big problem that needed a solution, so they funded us. Grand Challenges Canada and the Gates Foundation were our first funders with $100,000 grants. That was enough for us to get it on the market — and on babies — within 12 months. So the grants and the funding up front made those aspects of creating hardware much easier for us. And then our Saving Lives at Birth award enabled us to cost engineer, find alternative vendors, and build a rechargeable version.

The name Bempu — what’s the story behind that?

Our first device was a baby temperature monitoring band — that was the name of the device — and I made this little video on my computer, and the ‘B’ in “baby” and the “EMP” in “temperature” got underlined, and it kind of went together, BEMPU. And in Karnataka, where we are, a lot of the words end in that “ooh” sound. I showed that video to the doctors I was interviewing, and they all put me in their phones as the ‘Bempu guy.’ And it stuck.

The public health care system in India is a huge market for medical devices intended to serve low-income populations, but like other public procurement systems in LMICs, there are still significant barriers to adopting home-grown innovations. Tell us how you approached that challenge.

The Indian government cares for about a tenth of the world’s babies — 140 million babies, and about 14 million will be born in government hospitals in India. So you’re talking about scale.

We swung big to try to get into India’s national health program. And we got into a lot of the budgets, but we were not able to get it all the way to bracelets on babies. We kept our private business in India going, selling to various hospitals. But that is not necessarily a cost profitable model. But in the meantime, we hit this sweet spot with UNICEF, and then through various other public health partners or implementers. And that’s where we saw this explosion of growth.

What other products are coming out of Bempu?

Are you familiar with ‘kangaroo care?’ This is holding the baby close to your body, so there is skin-to-skin contact. It helps newborns regulate their temperature, among other things. There’s a huge initiative around that, across the world and across LMICs. But what we found is that mothers or fathers would do kangaroo care for a couple hours in the hospital and then they’d go home and wouldn’t necessarily do it. But doing it maybe eight hours a day for 30 days has shown to have these amazing improvements for the newborn. So we developed the KangaSling, which is an innovative garment that makes it very comfortable to do kangaroo care for long periods of time. It’s the only kangaroo care garment with built-in hip support and a front flap that makes it easy to take the baby in and out and very easy to breastfeed.

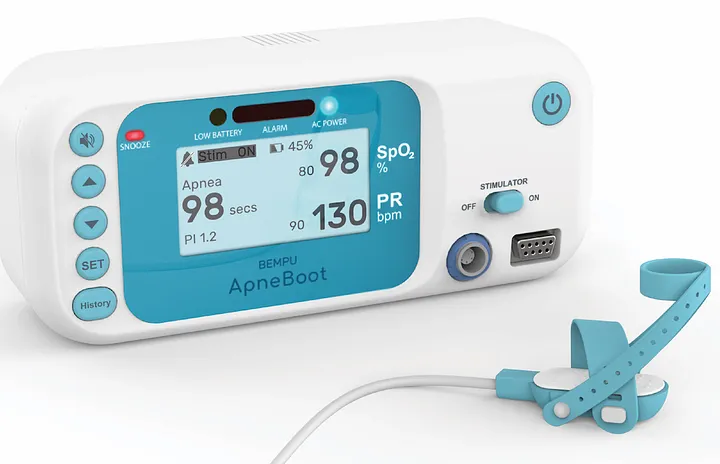

We also invented the ApneBoot, which is a NICU device that is fitted to a newborn’s foot. It has a sensor that detects when the baby stops breathing, and then starts vibrating to trigger the nervous system to begin breathing again. We launched during COVID and it’s actually been a big hit. We’re finding that it fills a need for sure.

Looking back, what would you say helped you as an inventor move forward? What keeps you going?

My bosses at Johnson & Johnson knew the whole time that I wanted to get into this space. My first boss was awesome. He made me write a career statement — like a vision statement of where I wanted to be in ten years. And I wrote that I wanted to be developing technologies that improved health for the world. So it’s funny how that works out. And now, we’re hearing a lot of success stories of our products helping babies in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Benin. And that is so rewarding.

What would your advice be to future inventors and entrepreneurs who are passionate about working in the global health sector?

Addressing health issues—and even more, health issues in developing countries — is not easy work. We’ve had our fair share of failures, delays, and setbacks. But no one said this was going to be easy. Knowing that you got the chance to make someone healthier and happier, or getting a call from a parent whose baby was saved by your products, will keep you going and make it all worth it.

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.