As Earth Heats Up, This Inventor is Focused on Keeping Cool

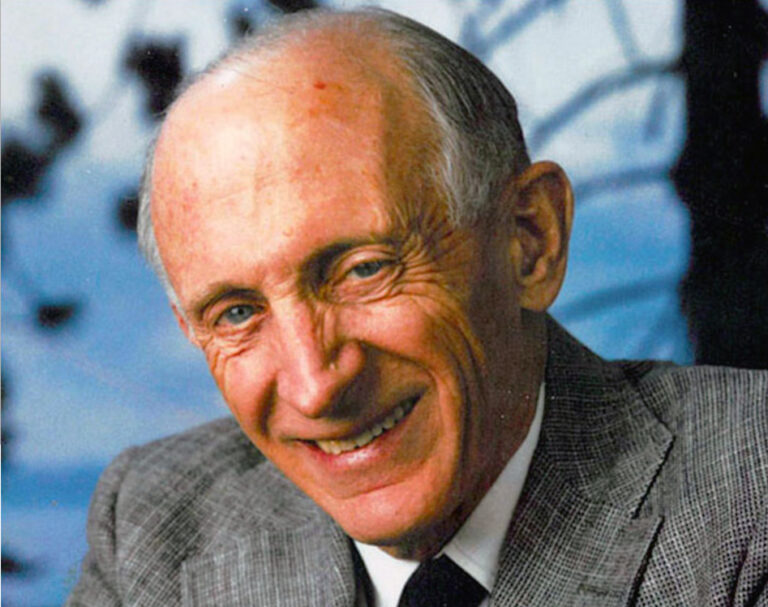

Engineer and entrepreneur Sorin Grama creates technology that makes refrigeration and air conditioning more efficient and less expensive.

min read

As the climate heats up throughout much of the globe, more and more people are dependent on air conditioning to live comfortably. But the very technology that helps them stay cool is contributing to the rising temperatures it’s trying to combat.

MIT lecturer and engineer Sorin Grama is focused on trying to break that cycle, particularly in the parts of the world most affected by climate change.

His latest company, Transaera, aims to make air conditioning cheaper and more efficient in low-resource settings. It was selected to compete in the Global Cooling Prize, a competition designed to innovate traditional residential air conditioning without the negative side effects.

Its goal is to spur the rapid development and commercialization of new technologies to improve the quality of life in some of the hottest places on the planet.

Transaera’s method uses a novel, sponge-like material that absorbs moisture. Humid air is much more difficult to cool – and traditional air conditioners, says Grama, have to perform two functions: dehumidifying air and cooling it. But to dehumidify, they have to overcool the air so that moisture collects and drips out.

“At Transaera, what we’re doing is separating the two functions – we’re taking care of the dehumidifying part with these materials that naturally absorb moisture,” he explains. “This means the air conditioner doesn’t have to work as hard to cool and dry the air. It just has to do the cooling, and that’s where the energy and cost savings come from.”

His solution has the potential to reduce energy consumption by as much as 60 percent as compared with standard air conditioners, lowering both upfront and operating costs for its users.

Although Transaera didn’t win the Global Cooling Prize awarded this April, it earned a spot among the finalists. “We’re very proud of the work we did,” Grama says, which even included supervising the installation of the prototype in India remotely by livestream because of the pandemic.

“The winners are some of the biggest corporate players in AC, and we’re a tiny startup. The fact that we didn’t win is like throwing fuel on the entrepreneurial fire – it’s actually quite motivating.”

Grama looks at climate change as an opportunity for startups like his. “It requires a completely different thinking,” he says. “That’s what allows small teams like Transaera to come along and say, I think we can do this differently.”

They’ve already developed new designs and iterations, and have even received interest from large AC manufacturers to incorporate Transaera’s ideas into their designs.

“The Global Cooling Prize put us on the map and gave us some credibility,” says Grama. “It’s actually opened up a lot of doors for us.

Transylvania Transplant

Grama is originally from Romania. When he was 18, his family moved to Cleveland, Ohio, to join other family members who had already come to the U.S. Though Grama attended high school in Transylvania, he did a repeat in Cleveland so he could learn English. “I was sort of parachuted into another high school because I didn’t speak the language very well,” he said. “It was a tough year, but it was a good idea in the end, I was able to get my footing and learn a bit about the American culture.”

Indeed, Grama quickly picked up English — and quickly discovered that many of his American classmates were more interested in football than in physics. “We didn’t have sports in our high school in Transylvania,” he says. “The coolest kids in our school were the ones that scored high in math competitions.”

Grama himself was a whiz at math. After attending high school in Cleveland for a year he went on to study engineering at Cleveland State college. He had always wanted to be an engineer like his father, who was a talented electrician.

After working at various companies across the U.S., Grama decided to make the move to earn his Master’s of Science and Management at MIT. The program appealed to Grama because it combined engineering with business — a pairing that would end up serving him well.

He graduated from MIT in 2007, and quickly found himself flexing his entrepreneurial muscles. He became an entrepreneur-in-residence at the school, and began working with students who were building solar power concentrators to generate power and hot water for schools and clinics in Africa. Grama joined them to help with business planning, but ended up co-founding a company called Promethean.

A Career in Cooling

Like Transaera, Promethean was also centered on cooling – but specifically, cooling and refrigerating milk in rural India, where dairy is a major industry. It grew from a project on solar power while he was a student at MIT. And while it was his first successful company, it also taught him a valuable lesson in failure.

Grama set out to solve a problem facing dairy farmers in rural villages: they needed to keep milk chilled to prevent spoilage before it could be collected for distribution and sale. His original design was for a rapid milk chiller that ran on solar power, which was meant to circumvent frequent power shortages and unreliable energy from the grid.

“We designed them here in the United States with our own U.S.-based thinking and supplies,” he says. It wasn’t until Grama and his team went to India and presented the device to their first customer that they realized their design made no sense for the local context.

“And the day after we installed it, he looked at it and said, this won’t work,” he recounts. “It’s too big. It’s too expensive. How am I going to put all these solar panels on every roof in 8,000 villages where I collect milk?”

After what Grama describes as a spectacular failure, they started over. He moved to India, and his team rebuilt the chillers using local materials and working with local engineers. He shifted his approach from solar to using power from the grid – but with one key difference.

“When that failure happened, it forced us to reevaluate everything – and we realized that the energy storage was the actual innovation,” explains Grama. “And then we drilled into that much more deeply, and that became the ultimate solution to this problem.”

Today Promethean has installed thousands of milk chillers across India, and operates in Africa and Bangladesh as well.

So the lesson, Grama says, is that creativity and innovation can come out of failure. “When we hit a wall with something, I know we’ve gone off the beaten path – and we’re now into the exploration phase of something that could be revolutionary.”

But as an untested, hardware-based invention, Promethean initially faced challenges in attracting investors. It took a range of support from a supportive ecosystem of funders – including The Lemelson Foundation, VentureWell, the National Science Foundation and USAID in the U.S., and Villgro in India – to help incubate the initial idea through the stages of product development and commercialization.

When Grama’s not busy designing game-changing cooling technology, he teaches and lectures at MIT’s D-Lab, which is focused on addressing global poverty challenges. In his course, D-Lab Design, he focuses on product design for emerging markets and the developing world. “I tell my students, get your boots on the ground and work within the local constraints, really understand the cultural context.”

That’s a proposition that has become more difficult during a global pandemic. But it has also led to more opportunities.

He describes one project where students were helping design a bicycle carrier for street vendors to transport hot liquids like coffee. “In a normal year, the students would build it and test it here, but we couldn’t get into the workshop,” he says. So they sent the plans to Uganda and engaged a local fabricator.

“They built it, they sent us photos, all that stuff was great,” he says. It helped build capacity in the local market, while teaching his students how to collaborate remotely. “I think that was a better outcome in the end.”

So what’s next for this inventor and entrepreneur?

“I’m inspired by working on pretty tough problems, things that might impact billions of people,” Grama says. And despite tackling large challenges, he sees fantastic opportunities for inventors to make targeted innovations that have impact at scale.

“Small improvements in a few things can go a long way.”

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.