Envisioning a Safer Eye Exam

min read

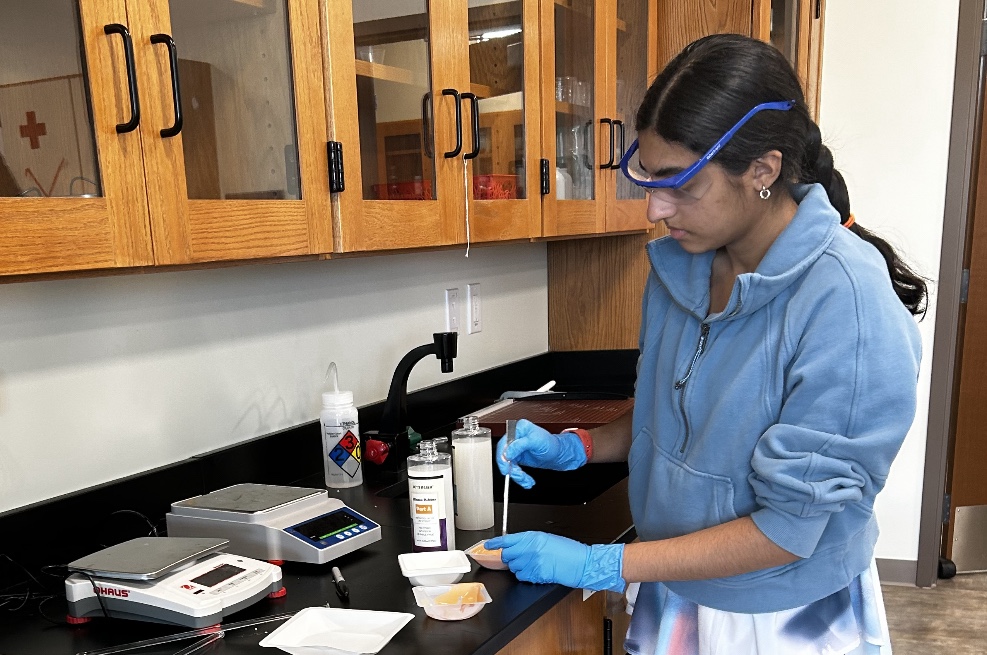

This young inventor created a synthetic model eye to help medical students train for optical procedures.

With more than two million working parts, the eye is considered the second most complex human organ after the brain. So how can medical students train for treating such a complicated and sensitive part of the body? That’s the question that inspired Florida high schooler and amateur baker Sonia Patel after her grandfather was diagnosed with glaucoma.

She decided to create a synthetic model eye that would allow medical students and medical residents to practice procedures without fear of injuring their patients. Her invention won her first place for high school seniors at this year’s U.S. Nationals for Invention Convention Worldwide run by The Henry Ford, as well as The Lemelson Foundation’s Invention Award for Societal Benefit.

We recently talked to Sonia — who is now a student at the University of Pennsylvania with an interest in pursuing ophthalmology — about her inventor’s journey, and the similarities between inventing in the lab and trying out new dessert recipes in the kitchen.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get involved in STEM?

I’ve always been interested in the engineering aspect of things. When I was younger, I liked to play with Kapla blocks and then Legos. I also grew up baking, preparing cakes, banana bread, and cookies. I’ve always been fascinated by building and creating things — adding things together, just like making a dessert.

In high school, my ideas developed towards the medical route. I decided I wanted to help medical students by providing a synthetic device for them to essentially practice on and work towards reducing surgical complications.

How did you get interested in the workings of the eye?

My grandfather’s glaucoma diagnosis made me interested in the field of ophthalmology. I accompanied him on one of his doctor’s visits and asked the physicians how one learns to check eye pressure. They essentially relayed that they have limited practice tools and synthetic models, resulting in practice of applanation [or measuring the pressure inside the eye] colleagues. I set out to increase the options of tools they have available to train.

“Always be on the lookout for problems. Begin with smaller problems, look for minor solutions, and you can work your way up from there.”

How did you want to improve the existing options?

The synthetic eye models currently available for training are expensive, around $600. They’re almost too expensive for medical residents to afford, often single use, and target a limited amount of procedures. I decided to create a model that would allow the residents and clinicians to practice various procedures on a model numerous times.

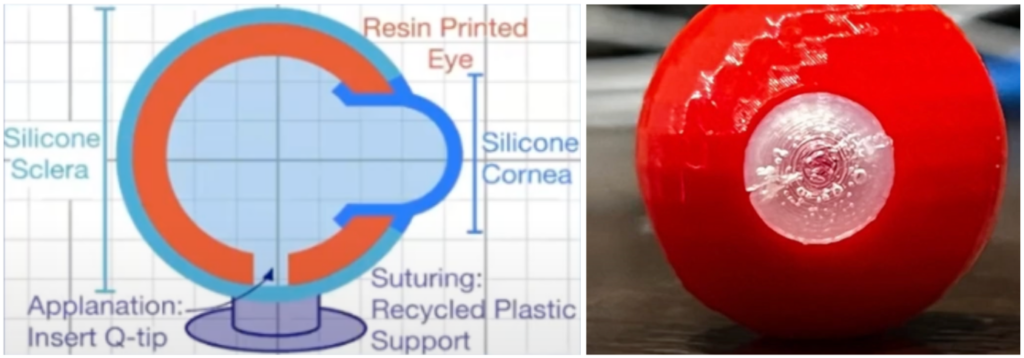

How did you go about creating a simple model for something as complicated as the human eye?

In terms of building and designing the model, I tried to make sure that it incorporates the same dimensions as a normal human eye, as well as the essential features of an eye to best simulate ophthalmic surgery. I used my school’s makerspace, which allowed me to tinker with 3D printing and resins for various iterations.

How did you get input from medical professionals for your device?

I was first able to reach out to clinicians at an American Society of Retina Specialists (ASRS) conference. Additionally, I met a couple of residents who were at Stanford. Later on, I reached out to Will’s Eye Institute to evaluate the model so that I could improve it. It was a very valuable experience hearing advice from trained professionals and seeing what they would want in a training tool. It was very helpful for next steps, like adjusting the model’s size to replicate eye muscles.

What were some of the challenges you faced as you developed different iterations of your device?

Creating the molds was a challenge as it was a very intricate, multi-step process. Adjusting the models and filaments used helped me work towards problem-solving. Essentially, it just grew in complexity. Initially, I started with an eye, and then started adding other components of the eye itself.

What’s your hope for this device?

I hope this eye model will be used in residency programs or medical schools, and ultimately reduce surgical complications for at least a couple procedures. In addition to that, it could be used in clinics around the world that lack significant resources. Given that it’s a cost-effective model, it could be very beneficial.

Who were your mentors?

The head of research at my high school, Mrs. Percivall, introduced me to the research program and got me started. Additionally, my mom was always there to support me as my number one fan. In terms of getting the device out there and having residents look at it, physicians were supportive and provided quality feedback.

What is your advice to other young inventors?

Always be on the lookout for problems. Begin with smaller problems, look for minor solutions, and you can work your way up from there. But also, don’t give up on an idea despite the challenges you may encounter. You have to learn to be patient, and not let one misstep affect the larger outcome of things.

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.