Envisioning the Future of Education

min read

Dr. Yong Zhao offers steps to help create a more diverse and inventive education system.

Imagine an education system in which every child — regardless of race, gender, ability, or economic status — could realize their full, unique potential and become part of the innovation workforce. Instead of gauging success through standardized tests and benchmark assessments, schools would more heavily weigh soft skills, such as inventiveness and problem-solving, collaboration and creativity.

This is the system that Dr. Yong Zhao is striving for. A Foundation Distinguished Professor in the School of Education at the University of Kansas and a professor in Educational Leadership at the Melbourne Graduate School of Education in Australia, Dr. Zhao is an internationally recognized scholar and speaker on education reform. He has just published a new book, “Learners Without Borders: New Learning Pathways for All Students,” that advocates a transformational agenda for education reform.

Reinventing education, says Dr. Zhao, will require a rewiring of not only curricula, but also assumptions on what we’re trying to instill in our students.

After starting a new school year full of uncertainty, we asked Dr. Zhao about his vision of the future of education — including opportunities to rethink the teaching of STEM and Invention Education — and what educators can do now to better motivate their students, cultivate creativity, and foster an inventive spirit.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is your perspective on the state of STEM education today?

Fifteen years ago, not everybody knew what STEM is, but now it has many advocates. As a term, it doesn’t make logical sense, if you think about it. The subjects in STEM are not categorically the same. But you get the idea — it’s trying to drive science and technology forward. If you want to market to politicians who don’t know much, it sounds really cool. And right now, STEM has had a huge media impact.

Other areas like liberal arts aren’t treated as equally important because they may not immediately bring the right economic value. My argument is that in the future, we cannot rely on just one field. In terms of priorities, whether it’s STEM or general education, we have to broaden the curriculum.

What do you see as the biggest challenges in education today?

You know, most countries in the world have an education system designed and managed by the central government.

In America, we have about 14,000 school districts, which means 14,000 possibilities of change, of difference. But America has this unhelpful idea of always looking at international assessments to show how much worse we are than other countries. None of the testing tests your innovation abilities, none of the testing tests what you can do. If we test you, we don’t test how good you are, we test what you’re missing. So you focus on a deficit.

There’s lots of attention paid to closing the achievement gap, what are your thoughts?

First of all, let’s analyze whether assessment has helped or not. All this testing we’re trying to do hasn’t really helped anybody. No Child Left Behind tried very hard to close the achievement gap, however, it has broadened the opportunity gap. Schools have been hiring test score experts and reading experts, but they’ve been cutting down recess, art, music, because they want to focus on literacy and numeracy.

Test scores are affected by family income that you cannot change. Poverty is the real cause, and not being able to read by third grade is just a symptom.

Exposure to different subjects is very important. But right now, our schools almost forbid that kind of exposure, particularly to poor kids. They’re forced to do literacy and numeracy so they can pass the test. So we’re making it worse for children to possibly engage in other things.

What is the downside of the system over prioritizing STEM education?

Schools today are too homogeneous. We want them to be able to do the same thing at the same time. Most people mistaken education as schooling. I’ve written a lot about the idea that schooling is by definition a creativity killing machine. The longer you expose students to schooling, the more likely you’re going to kill creativity.

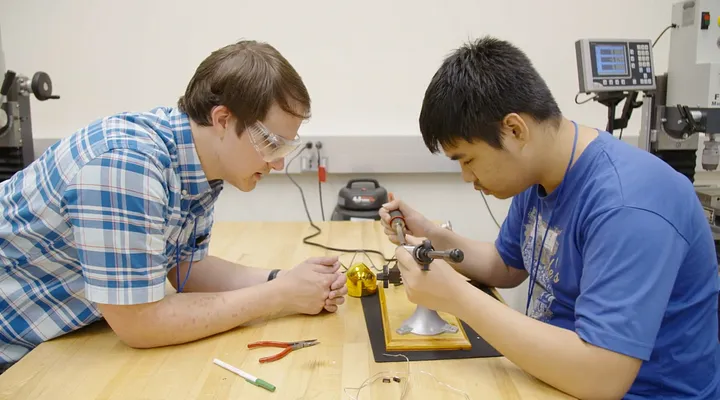

And inventive people do not really all come from STEM. Philosophy is also important, the humanities, literature, music. You need the whole person. We don’t need a society that’s just been a bunch of engineers driving it. You need a lot more than that.

Ultimately, I think there are two things. One is inspiration, and other is confidence. I think what we should do is we create thousands of options. When children run into one, they get inspired. You don’t know which moment your child will run into that will make them great. Can people inspire their children to say, I want to invent? Do children think that’s a possibility? I think if children feel you’re confident, they believe you can do it.

How can K-12 education better prepare students for the future?

First of all, we have to broaden the curriculum, because human beings can be talented in many areas. And that human innate talent is the basis for becoming great. As with any innovation, you start with creative options. We need to relax schooling to allow more possibilities, to allow schools to innovate.

If you look at children today, there are different ways of learning, different ways of thriving, different ways to succeed. And if you give children the confidence, the need, the desire, support their interest, you will have happy children.

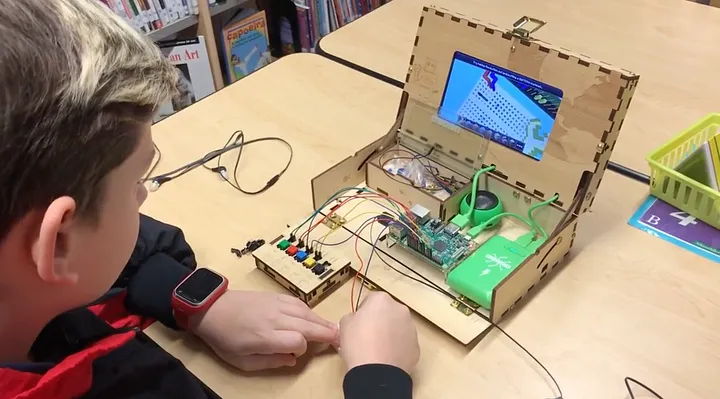

You start with children identifying a problem they want to solve. Children need to come up with their own vision. Then you say, maybe you want to read this book, maybe you want to watch this video, this gives some information. Then work with them towards a solution. The solution can be a product, an idea, an event, it can be anything. You drive children by wrapping the learning around these problems.

To be motivated, you must have autonomy, you must have choice, you must have voice. You also have to feel that you belong and that you are competent. And if a child is interested in doing something, they will be so motivated and so engaged that it will be hard to get them home for dinner. That’s called a moment of flow.

This is a big shift in our thinking about children and the possibility of change that can happen if we really want to create a culture for Invention Education.

What role do teachers play in your vision of a better education system?

The first thing I think we should acknowledge is that the majority of teachers want to teach well. The best kind of accountability is professional accountability — teachers hold each other accountable, as well as teacher organizations and school systems.

I also think accountability needs to shift, to focus on what kids do, and how are you are inviting them to rethink their life and their future. You look at if students are engaged, if a school is offering exploratory experiences.

Teachers have been treated as teaching machines. But we should really try to treat ourselves as human educators — we’re here to help children grow. Individual teachers can create options, opportunities for individual students. A lot of times in education reform, we like to do this for the entire school, for the entire system. That’s not going to happen. It’s really individual teachers, within the most stringent context, who can still do something.

There is all of this new technology available, so many resources to help children learn. This allows teachers to be the human educator, to guide them to move forward. What you need is a human being who understands with the child, who can make her happy, who can help guide her to a life in which she will find flow, a life she’ll enjoy. And we can evaluate growth by looking at are they engaged, are they confident, are they creative? We look at their learning experiences, instead of through their standardized testing.

How do you describe your vision of a future filled with more inventive kids?

Our current education system is like a beautiful rose garden. We want everyone to be a rose. So everything else is considered a weed. I’m envisioning instead a nature reserve, where diversity is worth cultivating. A nature reserve is much more sustainable, and much more productive than a garden. And we know that diverse teams work better, diverse cultures work better. Every species — and student — is worth cultivating.

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.