This College Inventor Is Making Medicine More Equitable

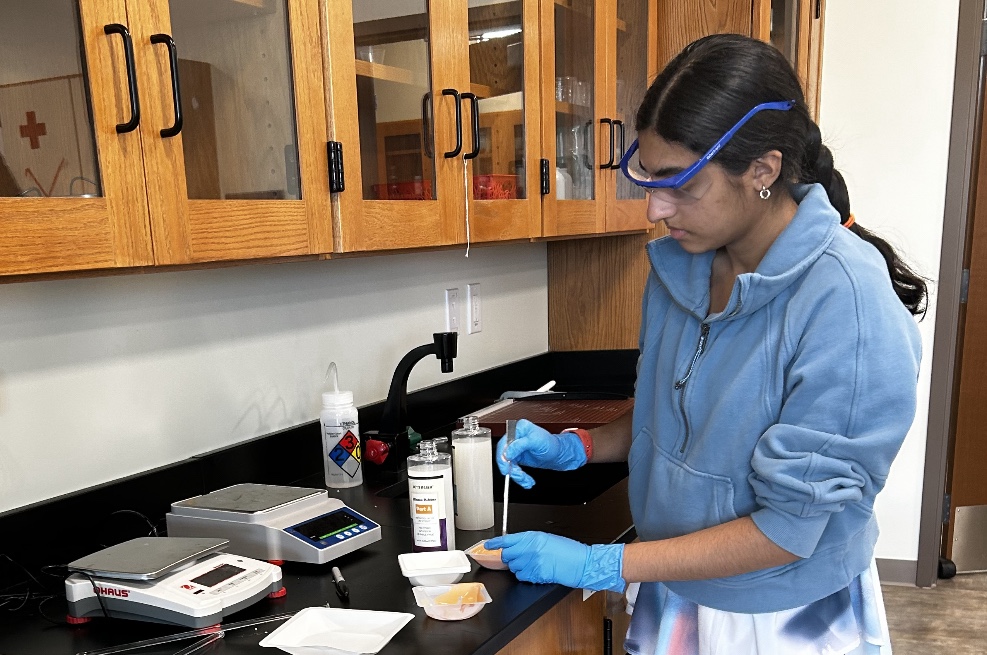

University of Iowa sophomore Dasia Taylor has created low-cost, infection-sensing stitches.

Inventor Dasia Taylor is one of those people who seems destined to change the world. At just 14 years old, she was consulting at Harvard on the topic of equity. Now 19, Dasia is in the process of patenting her first medical device — low-cost sutures that switch color if an infection has occurred, an equitable innovation on electronic “smart” sutures that could transform health care in underserved communities and save countless lives.

Dasia’s path to invention began in 11th grade at Iowa City West High School in Iowa, when she developed her sutures for a science fair project and ended up winning at state and national competitions. Since then, Dasia has received national attention, appearing on the Ellen DeGeneres Show and in many news articles showcasing her invention. But her favorite part of her job, she says, is the volunteer work she does at elementary schools back home. “It just makes my heart happy,” she says.

And Dasia’s heart is all about equity. Her mother, who was 18 when she gave birth to her, raised Dasia by herself. “In a sense, she and I grew up together,” Dasia says. “Everything she was learning, I was learning. And honestly, I was learning about all the inequities that existed.”

Then, when Dasia was in eighth grade, fighting for equity became even more personal. It was 2016, and the police shooting deaths of multiple Black men, including Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and Eric Garner had sparked nationwide protests and racial reckoning. Dasia had joined a competition called the Black History Game Show and with her team — and her teacher’s support — she made a Black Lives Matter sign and put it up in a busy hallway of her school. “But within passing time, which is about four minutes, it disappeared,” she says. The school principal had taken down the sign. That experience propelled Dasia to focus on K-12 equity, and fuels her outreach at schools in her hometown. “There have been a lot of personal experiences that I’ve had,” she says, “and as I get older, they may come less, but they come harder.”

Dasia’s invention stems from her focus on equity, and from an early interest in medicine. “When I was younger and I got my first taste of Grey’s Anatomy, I remember slicing open my teddy bear and sewing it back up with a needle and thread,” she says. So for her science fair project she knew she wanted to do something within the medical space — and then she read a story that ignited the spark. “I found this article about these high-tech smart stitches,” she says, “and I was like, ‘Oh, this is so cool.’ But my equity brain was like, ding ding ding, this is not equitable.”

After spending a few days gathering her thoughts, Dasia landed on the idea to make stitches that change color. “I had no science fair research experience,” she says. “As someone who didn’t know what the limits were, this was really important, because I learned everything from scratch.”

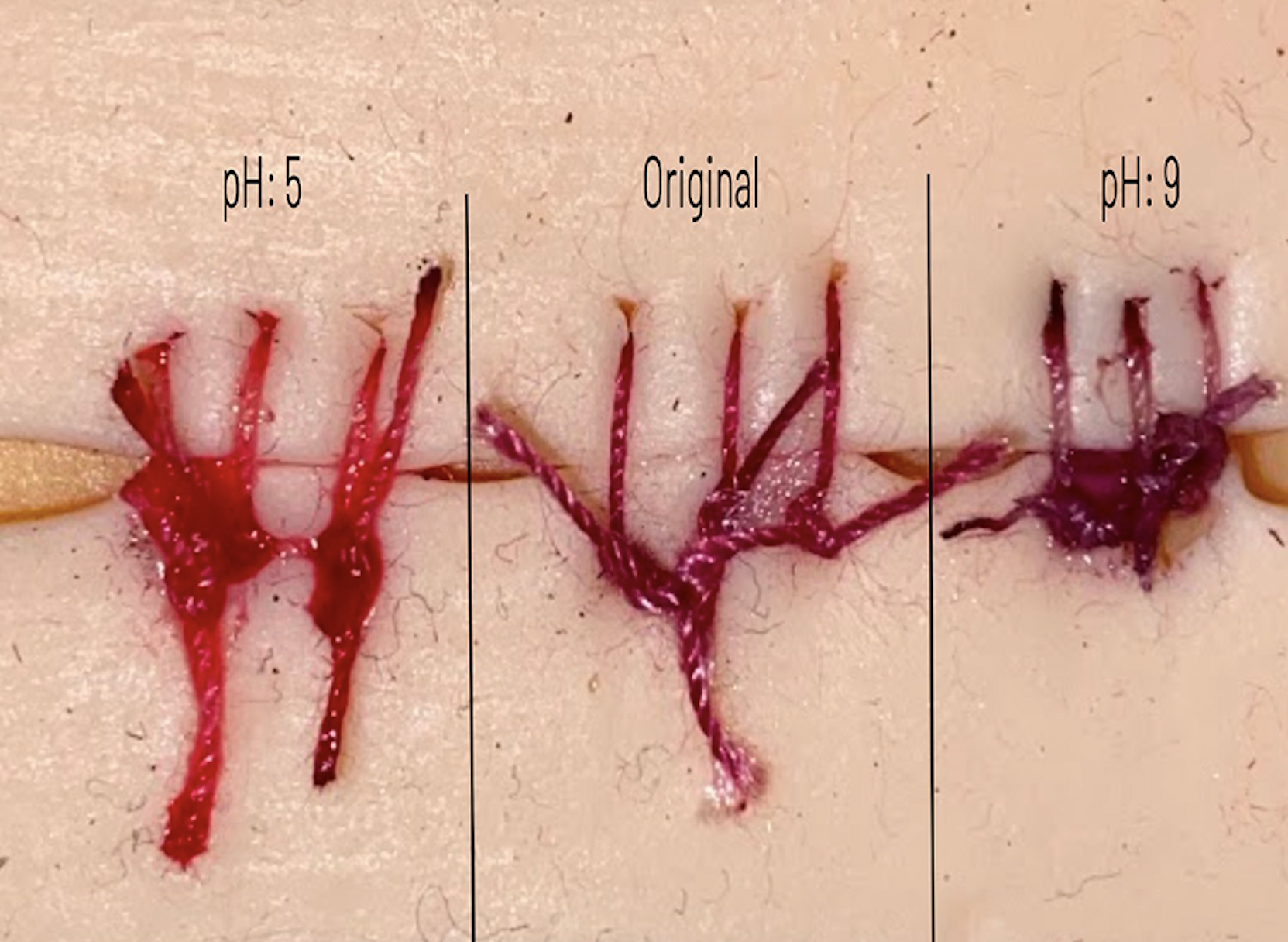

Dasia’s teacher told her about something called a natural indicator — a substance that can be extracted from plants such as beets, red cabbage, and blueberries, and used to reveal the pH of another substance because it changes color — and, she says, she went down “the research rabbit hole.” She researched the pH of a wound, and used the scientific method to find a plant that would indicate when that pH changed — in other words, something that would show when the wound becomes infected. The plant that met all her criteria? Beets. “I’ve rocked with them ever since,” she says.

While she works on patenting her color-changing sutures, Dasia has been busy developing something else: her company, Variegate, which she founded this year to support her product. “Variegate means to change color,” she says, but another facet of the definition is “to diversify.” “I chose that name in particular, because of my equity work, and it was really important to me, being a Black queer founder, that my company be a diverse space.”

Though seemingly always upbeat and full of drive and enthusiasm, Dasia is of course, familiar with the frustrations that come with being an inventor. On her down days, she says, she calls her mother. “She always told me, you can do anything you put your mind to. And I feel like I’m living proof of that.”

Dasia also emphasizes the importance of mentors in her life, many of whom are her teachers. “I attribute a lot of my success to the people I’ve met and the things that they’ve taught me,” she says. “Because we all have to learn from somebody.”