Transforming the Game with Invention

min read

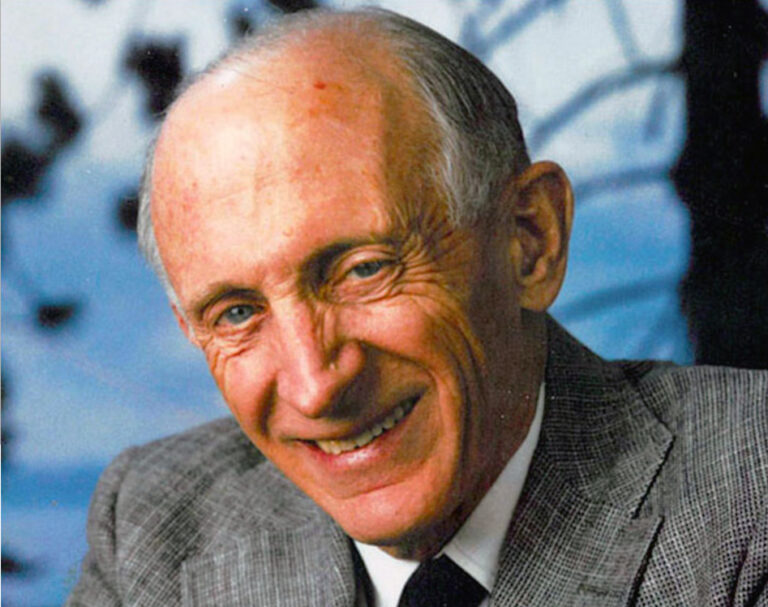

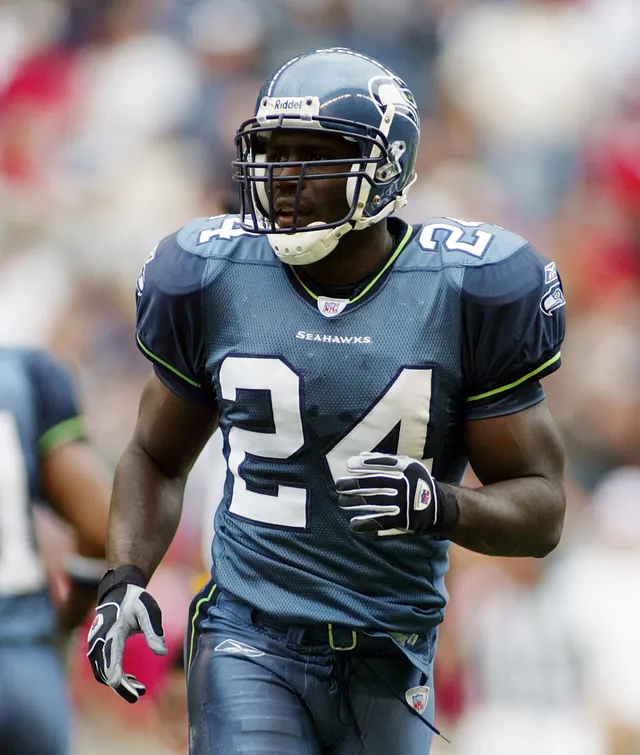

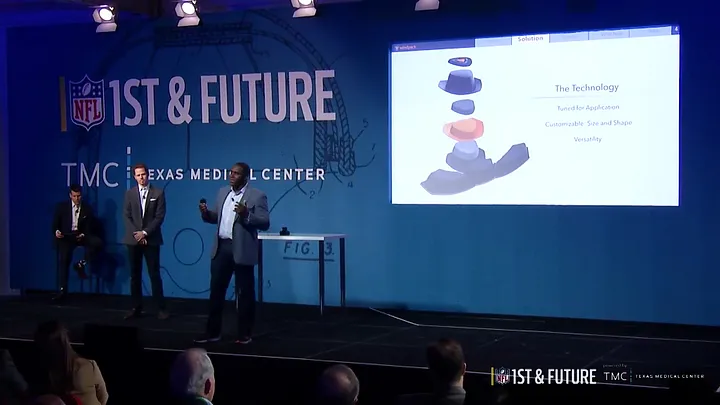

Shawn Springs, CEO of Windpact.

This former athlete turned entrepreneur and inventor is creating new sports technology to improve player safety.

Who can be an inventor?

A dynamic new exhibit at the Smithsonian’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation is posing that question through a unique lens, and the answer is…anyone and everyone, including athletes!

“Change Your Game” uses the world of sports to examine how invention and innovative technology play a role in athletics.

The interactive, bilingual exhibition features inventions made for, and many times by, athletes — from Gatorade to innovative skateboard and snowboard designs to prosthetics and adaptive devices that make sports accessible to everyone.

The “Change Your Game”/ “Cambia tu juego” exhibit in the Jerome and Dorothy Lemelson Hall of Invention at the National Museum of American History in Washington, DC. (Credit: Smithsonian Institution)

Featured within the exhibit is former NFL player Shawn Springs. After thirteen seasons playing professional football, he decided to pursue a new path to help solve a key problem in his sport: the high prevalence of concussions and traumatic brain injuries. Inspired by the foam padding found in infant car seats, he founded Windpact, a company developing advanced impact protection technology for athletic helmets to ensure players’ safety.

Springs’ journey from the football field to the lab and board room is just one example of how individuals can use their personal experiences and unique expertise to make a positive impact through invention.

The Foundation spoke with Springs after the launch of “Change Your Game” to learn more about his own inventor’s journey, and the similarities he sees between invention and athletics.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What were your early education experiences like? Were you always inventive?

Most kids have a humble curiosity. They always wonder how something is made. I was for sure one of those kids. My early years growing up were in Williamsburg, Virginia, in very small classrooms where we were encouraged to learn and be outside.

How did your teachers impact you?

They gave me opportunity, both encouraging and challenging me. I had a fourth-grade teacher, Ms. Scott, who was one of my favorite teachers because she would encourage us to see what limits we could push, so that we weren’t afraid to fail.

That came from my family, too — at an early age, people poured encouragement into my life. It’s important to give a young person the space to make a mistake and say that it’s okay to fail. Those aren’t bad things. That’s how you learn.

Your dad was also a professional football player, and you followed in his footsteps. But you’ve shared that both your parents stressed the importance of education in addition to sports. What were your academic interests in high school and college?

I was fascinated with architecture. In high school, I was probably just as passionate about design as I was about playing sports. I went to college for business marketing first and then got a degree in sociology, but I was blown away with how an idea can become reality, whether it’s a new product or a building.

You had a very successful career in the NFL, but were you also thinking about what would come next after retiring from sports?

One of the things that my dad taught me was to leverage football. Understand that it’s a gift that you can run fast and do some amazing things out there, but that doesn’t last forever because your body ages. Take care of your mind and always try to learn and network. I had a thoughtful approach to developing relationships for the future. And that all came from my father telling me that football is not forever, it’s a stepping stone.

Shawn Springs on the field playing professional football in Washington, DC (left) and Seattle (right).

Your time playing football for the Seattle Seahawks came during a significant period of growth for Seattle. How did being in that environment influence your perception of the technology industry and innovation?

When I went out to Seattle, I was drafted by Paul Allen, who co-founded Microsoft and was owner of the Seahawks. At the time, Seattle was a small, big city — a pretty tight-knit community where people were excited about innovation. Microsoft was doing some amazing things, Amazon was just coming on, Starbucks was kicking off. And they were all within arm’s length, where you knew somebody who knew somebody who could get to somebody you needed to know. Having a leader like Mr. Allen and seeing the way Microsoft changed Seattle, it inspires you.

How did you make that transition from sports to technology and find the problem you wanted to solve?

By my tenth year in the League, I noticed there was a lot of noise around traumatic brain injury. I became curious about why the technology that my father wore in the 1980s was the very same technology that I was wearing in the NFL more than two decades later, and I was hoping that my kids wouldn’t be wearing this same technology. My sons, like I did with my father, took a particular interest in football and wanted to play in college. And right then and there, I knew it was a problem I wanted to solve — to make the game safer for the next generation of athletes.

What was the inspiration for the Crash Cloud™ padding technology and the development of your company Windpact?

An executive from the driving safety industry sent me a brand new infant car seat that was designed to protect a baby’s head from side impact in crashes at 40 miles per hour. The technology both absorbed and dispersed energy, so not only did it take the impact, but it was able to push it away from the head. I just thought that was genius. I started to get into material science, and meeting automotive and aerospace industry leaders from Boeing, Honda, Ford, GM, and Harley-Davidson to see how they were developing new products.

And then I thought, isn’t football like a series of car crashes? Could this technology be repurposed? So that’s what we set out to do. To simplify it, just imagine an airbag with a mattress or foam inside — this unique combination allows us to solve for a variety of impacts.

How did your experience as an athlete influence your approach as an inventor?

I had a competitive advantage because I was the user of the product. Since I actually wore the helmet, I understood the challenge and how difficult it was to solve. Athletes don’t want a helmet that’s too big, but just a little bit of foam doesn’t protect from those large impacts. I’m not an engineer, so I wanted to find the people who had a unique skill set that could solve this problem. That meant going to universities, going to the automotive industry, asking questions and looking at this sports problem from a more holistic approach.

Did you experience any skepticism as an athlete turned entrepreneur and inventor?

100%. One of the things you learn about business is you can have great ideas, you can have a great business plan, but if no one believes that you can execute on it, you’ll face challenges when you’re trying to raise capital. People are like, “Why would I bet on you if you didn’t go to school for this.” Well, I thought maybe that’s the reason why we haven’t solved this problem, because you’re betting on the people who don’t understand what it’s really like to experience it.

You work with a larger team at Windpact. Could you tell us more about the importance of having a collaborative approach to invention?

Invention doesn’t happen in a silo, and it doesn’t happen by yourself. To me, the best inventors are those who can see all the connections in solving a very difficult problem. Let me take a guy who does modeling, a person from the automotive space, an engineer who is already working on this, and combine them with the insight that I have as a professional athlete. That’s what makes it unique, when you can bring together diverse thinking and collaboration to create an amazing solution.

What other areas besides football is Windpact developing impact protection padding for?

We’re also in baseball, cricket, and lacrosse — even hip protectors for the elderly. One of our biggest opportunities is in the military space, making padding solutions for the next generation of soldiers, and solving for ballistic impact with about an inch of foam.

How did it feel to see you and your colleagues’ work at Windpact being featured in an exhibit at the Smithsonian?

Surreal. I was proud that I was featured, and that there was finally some recognition for the others who put in long hours, long nights, and made sacrifices to take their product from ideation to commercialization.

It is also a reminder that anything is possible if you put your mind to it, and you believe that you could be the difference and change the game — regardless of your technical background, gender, or ethnicity. I think that’s the driver for a lot of innovators and inventors, saying, “How do we make the world better?”

What is your advice for other aspiring inventors? What else does it take to be a game changer?

Dedication, discipline, and resilience. You’re going to lose a lot. You’re going to fail a lot. But those who can endure the failure, understand and embrace the challenges, take them as learning experiences — that’s very similar to what we do in sports.

You’ve seen those games where you think the game is over, but you come back and you win? Those are the moments we live for.

Important Disclaimer: The content on this page may include links to publicly available information from third-party organizations. In most cases, linked websites are not owned or controlled in any way by the Foundation, and the Foundation therefore has no involvement with the content on such sites. These sites may, however, contain additional information about the subject matter of this article. By clicking on any of the links contained herein, you agree to be directed to an external website, and you acknowledge and agree that the Foundation shall not be held responsible or accountable for any information contained on such site. Please note that the Foundation does not monitor any of the websites linked herein and does not review, endorse, or approve any information posted on any such sites.